PRESIDIO OF MONTEREY, Calif. -- The Presidio of Monterey has undergone several distinct periods of change. One of the most active periods occurred during the Great Depression of the 1930’s. From 1934 to 1936 various federal agencies made extensive alterations to Soldier Field and the adjacent buildings and landscape. Heading up these efforts were the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and Works Progress Administration (WPA).

In an effort to move the United States out of the depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ policies created several agencies meant to employ out of work Americans. The agencies are often referred to as the ‘alphabet agencies’ due to the extensive use of their shorthand abbreviations.

“The main job (of the CCC) was to put Americans to work on conservation projects in the forests and National Parks, but they also ended up on military bases,” said Cameron Binkley, Defense Language Institute’s command historian. “(The WPA) was focused more on technical projects.”

The most prominent features of today’s Soldier Field are the result of 1930’s efforts. The concrete bleachers along Stillwell Ave were laid at this time. The formerly sloping Soldier Field was leveled to eliminate its natural incline and retaining walls were added along its borders. Both of these alterations have gone largely unchanged for over 80 years.

A recent brush clearing effort uncovered a unique section of the retaining wall along the base of Serra Ave where abalone shells were embedded by workers directly into the concrete. The sunrise once again shimmers off the mother-of-pearl shells as it did when the walls were first constructed.

Surrounding Soldier Field are rows of former barracks buildings which predate the depression, but received substantial structural changes to their originally raised, wooden designs. The men who originally constructed the barracks and the Quartermaster who oversaw the project had constructed similar buildings while deployed in the Philippines.

“It was a standard Army architecture modified in the Philippines, then further modified here,” said Binkley,

The depression-era workers added stone basements and concrete foundations to make these provisional structures permanent and more structurally sound.

Not all of the projects were strictly functional. Many agencies funded arts projects that also impacted the post. In California the State Emergency Relief Administration (SERA) was responsible for the distribution of federal and state funds to improve conditions and beautify the state.

“The state gave some money to put artists to work in California and the (command leadership) here at the time found out about it and wanted to get in on It.” said Binkley.

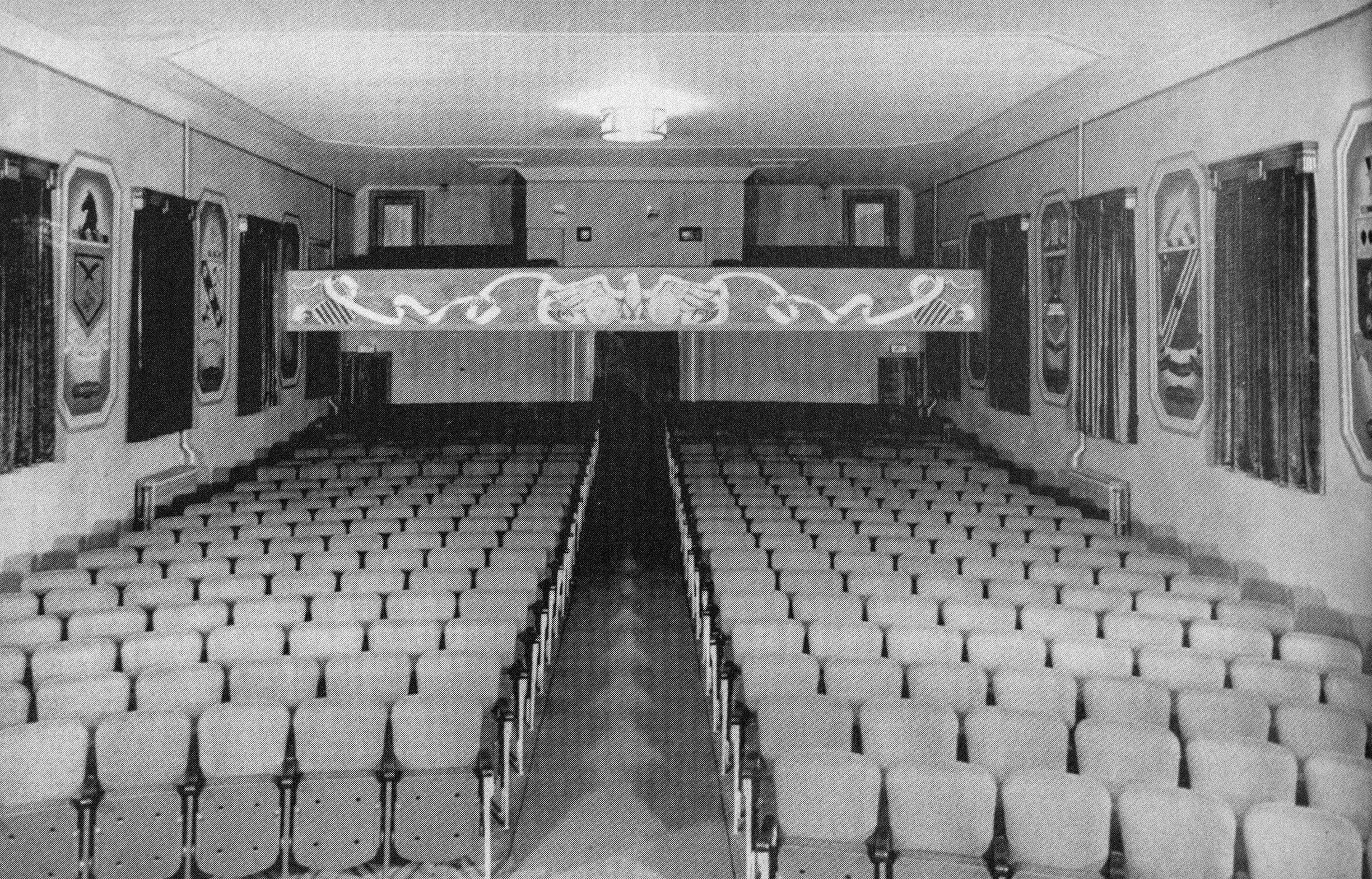

The original assembly hall, now the post theater, had its interior walls adorned with paintings of the coats of arms of Army units that had been stationed at the Presidio. Similar artworks were added to the interior of Lewis Hall, the period home of the Outdoor Recreation Center, depicting sports figures and murals of Army life.

The exterior of the theater was also altered with the addition of a portico on the front of the Spanish inspired building, in order to match the front of Lewis Hall. As part of the SERA arts project, hand-carved doors were added featuring military emblems, images of coastal wildlife, and classical theater symbolism. The door was the work of artist Carlos Ayala, who period accounts refer to as an ‘Aztec’, meaning of Mayan descent.

Unfortunately, at some point prior to the 1960’s much of the art was removed in order to modify the buildings.

“By that time, the mid-sixties, everything was gone,” with the exception of the intricately carved theater doors, noted Binkley. “The doors (are) the only thing that survives of the WPA art.”

As the depression was coming to an end and World War II was emerging on the world stage the public works agencies moved their focus from the Presidio of Monterey to Fort Ord. This period is referred to as ‘mobilization’.

Camps were constructed across Fort Ord and many of the buildings that remain today were built in the early 1940’s. Among those that still exist are the General Stilwell Community Center, former post chapel and Martinez Hall, the former headquarters of the post.

“They built a series of mess halls and latrines that were in the California Mission style.” said Binkley, but in addition to the obvious structural additions to Fort Ord, “They cleared a lot of brush out of the way. They did roadwork, utility underground installation, ditches... They did a lot of that manual labor work on a vast scale.”

During World War II these New Deal agencies were phased out and left military bases by 1943. Following the closure of Fort Ord, many structures of the era eventually fell into disrepair. New housing projects such as those in East Garrison have led to the demolition of many decaying CCC and WPS constructions. However, some of these 1940’s buildings were saved for their historic significance in partnership with developers, and are in the process of becoming interpretive history sites.

“They couldn’t build the houses without rehabilitating those structures, so they are protected and preserved.” said Binkley.

Other World War II era structures across Ord Military Community have been repurposed for community services and offices. One prominent example is Martinez Hall which is now home to the Veterans Transition Center.

While many of the remaining structures are visible across the Presidio of Monterey and former Fort Ord, the human element of the depression can also be seen if you know where to look. The personal touches like the abalone shells embedded in the concrete walls along Soldier Field, and the often overlooked badges and insignias for the CCC, WPA, SERA, and other alphabet agencies can still be discovered on many of their construction projects.

Social Sharing