FORT CAMPBELL, Ky. – The Screaming Eagles of the 101st Airborne Division have a long and storied history that dates back to Aug. 16, 1942.

But not many people know how it got its name or know how one man fought to reclaim the name, 101st Airborne Division, after it was briefly changed for one month in the midst of battle.

As the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) prepares to celebrate its 78th anniversary, staff at the Brig. Gen. Don. F. Pratt Memorial Museum took time to reflect on five things that highlight some lesser known stories of the division and a few of its victories – big and small.

“There are older units but our patch, our name – we are the most recognized unit in the world,” said Capt. Daniel Herbster, division historian. “We were created as an elite institution and we still are 78 years later.”

Every year of the division’s anniversary is an opportunity to look back to see where the 101st came from and where it is going, said John O’Brien, Pratt Museum director and author of “A History of Fort Campbell.”

“With 78 years of history there are all kinds of stories that could be told, stories in training, stories in combat, stories in peacetime, stories about deployments to support the national humanitarian missions and picking out just five is a really difficult thing to do,” O’Brian said.

In an effort to tell the story of the division, the museum staff selected five lesser known stories including how the 101st became the “Screaming Eagles,” the name that irked the division for a month, Hellfire missiles, nuclear weapons, and a dentist’s quick fix.

Screaming Eagles

O’Brien said one of his favorite stories is how the division became known as the Screaming Eagles.

“We are the Screaming Eagles and everyone knows who we are but how did that nickname come about?” he said.

When the division was activated, its Soldiers went through several years of training before the division’s first operational combat mission. The Soldiers spent much of their free time participating in sports.

“Every regiment had boxers and baseball players and basketball players and one of the regiments, the 502nd, picked as a nickname for their team the Screaming Eagles,” O’Brien said.

The boxing teams gained attention at Golden Glove competitions while at Camp McCall, South Carolina, and while in England.

“The newspaper people, started referring to the entire division as the Eagle Division and then the Screaming Eagle Division,” O’Brien said. “So, it’s something that came out of the sports lore of the division and was picked up by local newspapermen who were reporting on how the division was doing in England before the invasion. The Screaming Eagles became the nickname for the entire division before Normandy.”

Name change

During the Vietnam War, the Army tested the integration of helicopters into an infantry division to give infantry units greater mobility. The 1st Air Cavalry Division commanded by Major Gen. Harry W.O. Kinnard was the pilot division.

“He had been a member of the 101st in World War II, and it’s for him our Kinnard warfighting center is named,” O’Brien said. “He was an expert in the use of helicopters in a tactical division.”

After the secretary of defense assessed the progress, he was so impressed with Kinnard and the 1st Air Cavalry Division that he told the 101st Airborne Division it must become an air cavalry division organized like the 1st Air Cavalry.

“What happened in essence is the division had to change its organization in the middle of combat in August of 1968 in Vietnam from essentially a paratroop division organization to this new thing called an air cavalry division,” O’Brien said. “A whole bunch of helicopters were added to the division and the division started fighting the war using helicopters in a particular sort of way.”

Because of that transition, the 101st Airborne Division was renamed the 101st Air Cavalry Division.

“The division commander at the time, Maj. Gen. Melvin Zais, was a proud, proud paratrooper and he was not going to give in to the 101st Airborne Division of historic World War II fame being called an air calvary division,” he said. “It took him a month but he fought with the chief of staff of the Army and eventually got the name changed back officially to the 101st Airborne Division.”

The compromise was a set of parentheses added at the end – 101st Airborne Division (Air Mobile). In 1974, the designation changed to 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault).

“For that one-month period, we were the 101st Air Cavalry Division and nobody liked it,” O’Brien said.

Hellfire over Baghdad

Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm were significant for the Army and the nation with a great effort to rebuild the military and restore confidence after the Vietnam War, O’Brien said.

Operation Desert Shield began in response to Iraq’s Aug. 2, 1990, invasion of Kuwait. To support the operation Soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) were among the first to deploy to Saudi Arabia. Five months later, division pilots fired the first shots of Operation Desert Storm.

“The first shots were fired in January of 1991 by a task force that was put together within the division, an aviation regiment at the time called Task Force Normandy and it was a company-size element,” O’Brien said. “It had Apache helicopters, accompanied by some Air Force helicopters, that did a really dangerous long-range mission, from Saudi Arabia to Baghdad.”

Task Force Normandy was under the command of then-Lt. Col. Richard Cody.

“He took his team into Baghdad and they had to fly below the radar the entire way,” O’Brien said. “It was a very complex flight in and of itself. And when they arrived in the Baghdad area, the first shots they fired were Hellfire missiles directed against the Iraqi Air Defense protection around Bagdad.”

Their mission was to take down the Iraqi air defense system so the U.S. Air Force could fly in without the threat of being shot down.

“Task Force Normandy slipped in secretly, took out, without exception, all the key components,” O’Brien said. “They hit all their targets and they slipped away into the night leaving a gaping hole that the Air Force was able to take advantage of for the air war that followed for the next month.”

The air war was the first component of Operation Desert Storm and it paved the way for the ground war that began Feb. 21, 1991, and would last about 100 hours.

“The choice of the name Task Force Normandy for those modern warriors harkened back to the division’s first combat mission in World War II, the invasion of Normandy,” O’Brien said.

As for the man who led the mission, he became Maj. Gen. Richard Cody, who commanded the division June 2000-July 2002, and later became the 31st Vice Chief of Staff of the Army.

Nuclear weapons

The 101st Airborne Division was inactivated in 1945 in Europe and was not reactivated until 1956.

“Its organization changed because throughout the 1950s there was a great reliance on nuclear power for our national defense strategy and the Chief of Staff of the Army Gen. Maxwell Taylor, had been the wartime commander of the 101st and he looked at how to reorganize the Army to fight on a nuclear battlefield,” O’Brien said. “What he came up with was a new organization for the Army that was called the Pentomic Army.”

The “penta” stood for a five-sided atomic capable division and “omic” came from atomic.

“Instead of having the traditional three regiments, two up, one back, the new organization for a pentomic division was five little airborne battle groups that could be spread out greatly on the battlefield so that one Soviet nuclear weapon could not take out two regiments up and one regiment back.,” O’Brien said. “That made a very compact target.”

The five groups would be supported by long-range fires, he said.

“The long-range fires included nuclear weapons,” O’Brien said. “So during this odd period where we were the 101st Airborne Division (PENTOMIC), every airborne battle group in the division had a battery of nuclear-capable mortars called the Davy Crocket Mortar, essentially a recoilless rifle that could launch 0.7 megaton nuclear projectile about 2,000 meters.”

Although fairly small, it was a “dirty bomb” meant to contaminate terrain so Soviets couldn’t roll through a contaminated area without suffering nuclear sickness, he said.

“We also had in the DIVARTY of the division, a battery of nuclear capable missiles called the Honest John and the Honest John was a 1-kiloton rocket that could add nuclear fires to the division’s capability.”

The division had nuclear weapons from 1957 to 1964 when the Army decided the Pentomic Army wasn’t working as hoped.

“Plus, the nature of the operations that the Army was to participate in under President Kennedy with flexible response caused the Army to change its organization from the Pentomic Army to a new type of organization, where instead of regiments or airborne battle groups, a new organization would have brigades,” O’Brien said.

Mortar platoon had four launchers and each launcher had a team of five crew members. The 101st Airborne (PENTOMIC) never deployed to combat. One of the airborne battle groups was deployed to Little Rock, Arkansas, by President Dwight Eisenhower in response to civil unrest after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling and the Arkansas governor’s failure to integrate Central High School.

“That was fighting for freedom at home,” O’Brien said. “So that period of time from 1957 to 1964, when we were the 101st Airborne Division (PENTOMIC) we had nuclear weapons as part of our organic division arsenal.”

Dentist saves day

After the Vietnam War, the 101st had about two years to make a transition from a gorilla counter-insurgency type of warfare to the “Nixon Doctrine.”

“What the Nixon Doctrine said is the enemy is potentially the Soviets in Europe so all our divisions had to be capable of fighting Soviet armored divisions in Europe,” O’Brien said. “And the 101st Airborne Division (Air Mobile) was not capable of doing that. So there was a transition to new equipment, new organization and new tactics that became known as Air Assault tactics.”

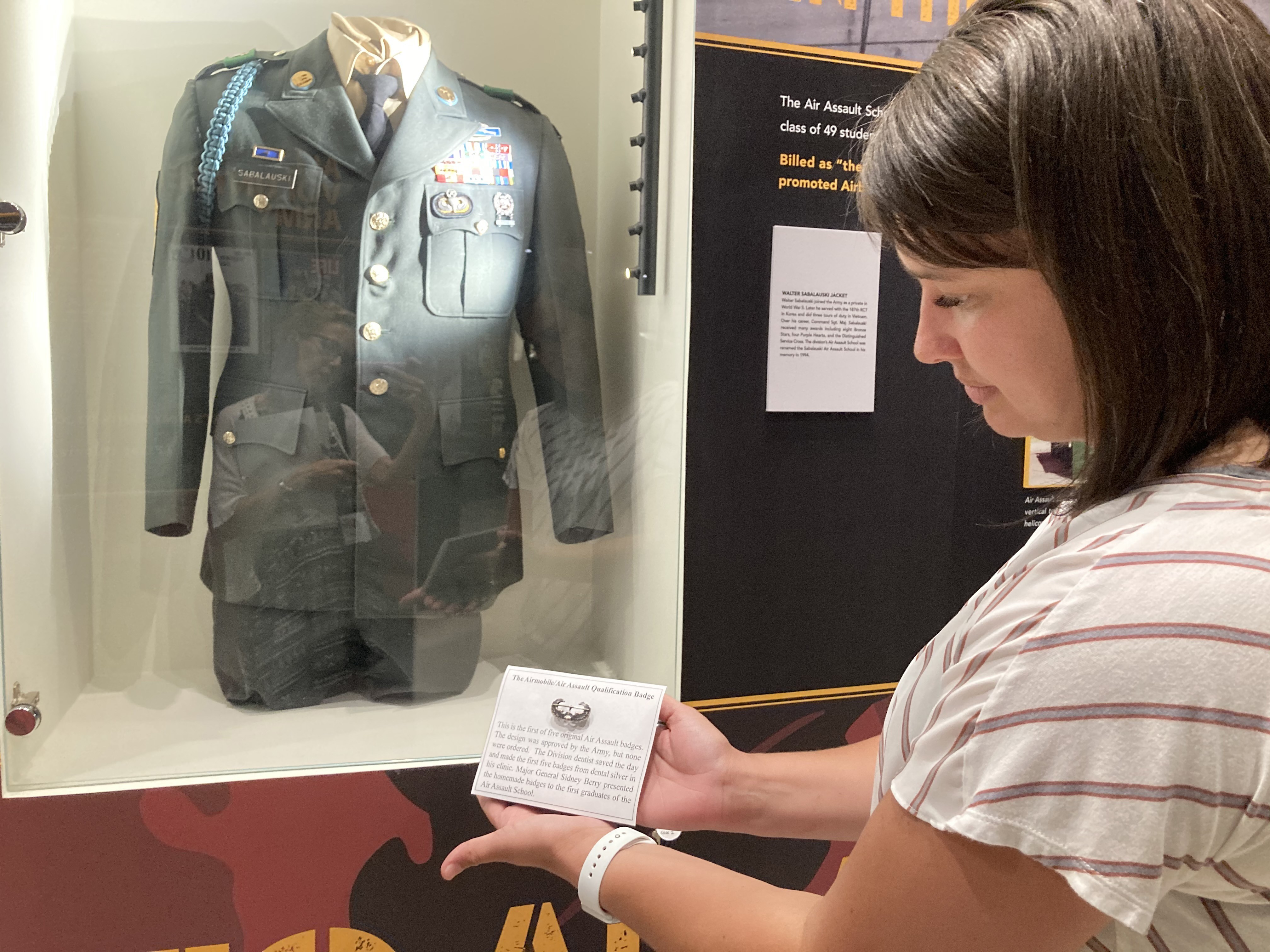

The 101st Airborne Division created The Sabalauski Air Assault School to teach the skills that would be necessary and developed a badge for graduates that was adopted by the Army in 1974.

O’Brien said the Army’s Department of Heraldry worked with the 101st to create the current Air Assault badge, that features wings with the front of a helicopter.

The cadre selected to train the Soldiers were made up of a major, a sergeant first class and three sergeants, and were the first to earn the Air Assault badge.

The then-division commander, Maj. Gen. Sidney Berry, wanted to have a big ceremony and make a big presentation of the first five Air Assault badges, but there was just one problem.

The day before the ceremony, during a rehearsal, it was discovered no one had ordered the badges.

“There were none,” O’Brien said. “Everybody went into a panic and the division dentist happened to be there because he was part of the division staff at the time and he looked at a picture of the badge and said, ‘No problem, I can make these tonight in the dental lab using the silver filling material. So, our first five Air Assault badges, two of which we have here at the museum on display, were made by the dentist who saved the day and Maj. Gen. Berry never knew the difference.”

Social Sharing